When Over 60,000 On Each Of 11 Days Flocked To See Olympic Swimming & Taylor’s Triple Gold At White City In 1908

Organisers of the U.S. Olympic Trials that have been underway in a stadium in Indianapolis this past week, have boasted of the biggest ever crowd for a swimming competition but the standard has belonged to London’s White City since 1908, unless you add “event featuring women”.

Yes, you read that right. Without ‘women’ in the sentence, the claim is a tall one. As Trials head towards their conclusion along with other events in Europe before the Sunday deadline for Paris 2024 entries, and this author heads off to the graduation ceremony of one of our sons, here’s a file to fill the void here at SOS for the rest of this day.

Organisers and participants in Indianapolis are rightly celebrating crowds of up to 22,000 people in their stadium pool venue each evening of Trials. Great news and a terrific showcase for swimming, hopefully one that feeds into the sport’s economy in a way that reaches athletes and coaches or swimming.

Back to that top line…

The biggest swimming venue and crowd ever was that assembled to watch the six male-only events held in the 100m tank dug into the infield of the White City Stadium built for the 1908 Olympic Games in London.

The maximum venue capacity was 97,000, and more like 80,000 at the time of the Games, with regular “full crowds of 68,000” reported as athletics and swimming overlapped. The swimming events were held over 11 days, from July 13 to July 25, the 19th, a Sunday, the day of rest.

So, at 60,000 a day, that 660,000 spectators tune into live swimming at the venue. Even at 20,000 a day (and it was way more than that in 1908), it would be 220,000, so, great job Indy venue but not a record, neither for a single session nor a whole meet.

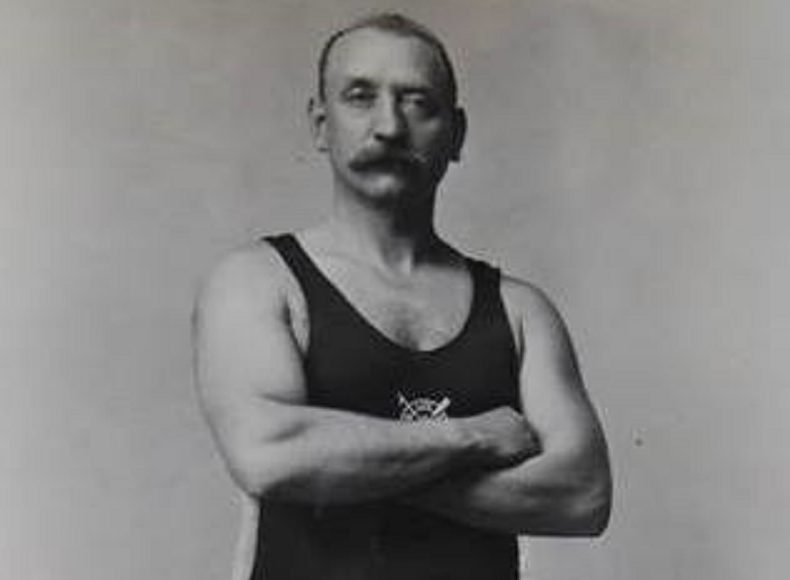

The London capacity was not meant to set a record for the ages and beyond but it was planned. When the British capital London was handed the right to host the Games in 1908, engineer J. J. Webster was called in to help William Henry, founder in 1891 of the Royal Lifesaving Society (RLSS), design the White City Stadium at Shepherd’s Bush that would host track and field, swimming and diving events as well as the finish of the first modern marathon (see footnote).

The pool was 100m long, 15m wide (17m in some references but the official plans state 15) and ran to depths of 1m 20 to 3m 70 at the place the collapsible diving tower was installed for the Olympics. There were no lane ropes, nor starting blocks at the time but it was state-of-the-art for its time and has a row of claims to being first, biggest and so forth to its name to this day.

Whatever records were set at White City, they did not include women swimmers, who only got a ticket to the Games for the first time at Stockholm 1912. So, U.S. Trials can at least claim a ‘biggest’ crowd at a competition for all swimmers if they doff their caps to the females athletes helping to entertain the masses.

It’s a line, along with other riders like “over nine days” and a number of others measures pertinent to the now but not the then, that USA Swimming might want to boast as The Parity in Paris Olympics loom on the horizon.

The Games next month will get underway with the same number of males and female athletes entered to compete for the first time in history. The sexes don’t have the same number of targets to aim at, men with the edge still, nor do women have anything like the representation in Olympic and International Federation governance that men with an extraordinary amount of time on their hands to serve as ‘voluntary executives’ do.

Still, progress is progress. Swimming venue are certainly a world apart these days and the Indy stadium where trials are being held in Myrtha Pools‘ temporary tanks do indeed mark progress and innovation. Like the temporary tanks, the 20-22,000 crowds in for finals in Indy, are neither the first nor the biggest.

White City Limits Beyond Anything That Followed

Back in 1908, “full crowds of 68,000 people” turned up to watch as athletics overlapped with the swimming, diving and water polo events. The venue was the first and last 100m pool, the first temporary pool after the foundation of FINA at the Manchester Hotel in London on the cusp of the Olympics in 1908, and remains the holder of the record for the biggest-ever swimming crowd at an Olympics or any other elite swimming event ever held.

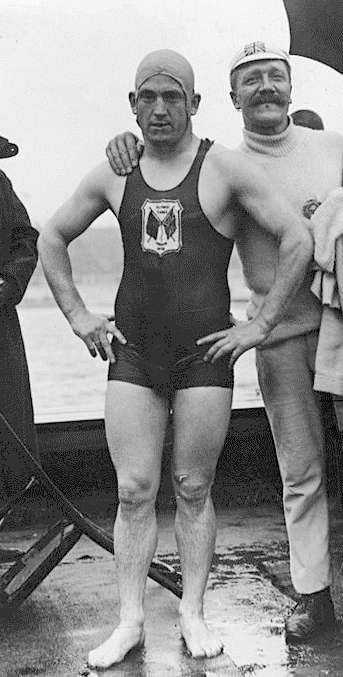

The swimming, which had previously been held in seas, rivers and, in 1904, a man-made lake, was a novelty and all the more popular for it. Crowds flocked to see home hero Henry Taylor race to three of the six gold medals up for grabs in the pool.

The other wins went to American Charles Daniels in a World record of 1:05.6 in the 100 freestyle and Germany’s Arno Bieberstein, the winner of the first Olympic 100m backstroke race, the 1904 Games having featured a 100-yards race in the man-made lake at St Louis. Only the first three finishers in each race were timed, in London, the rest simply given a placing.

Like the “biggest crowd” line, Taylor’s success in London is one that stands in the way of modern pioneering claims of “greatest haul” and so forth: his victories in the 400m, 1500m and in the 4x200m with teammates John Derbyshire, Paul Radmilovic and William Foster established World records in all three events.

That relay included others who hold records to this day: Foster remains the youngest-ever Great Britain team member to claim Olympic gold, at 18 years and two weeks; and Radmilovic was the first Brit ever to compete at five Olympic Games, as a swimmer and water-polo player, with golds in 1908, 1912 and 1920 and fourth places in 1920 and 1928.

Nothing Under the Sun, as Hemingway put it.

Well, not quite in all regards. There’s always a new line to write. A large section of the stand at London 1908 was covered but the venue was clearly outdoors, which would allow the U.S. Trials folk to boast a record for an “indoor” venue. Other Olympic swim capacities compared:

Berlin 1936, 20,000; Athens 2004, 23,000 but that total for three pools not the main competition pool alone, which was around 17,000; Beijing 2008, 17,000; London 2012, 17,500; Tokyo 2020ne, 15,000 (though Covid meant there was no crowd beyond those taking part); while Brisbane 2032 envisages about 17,000, too, after Los Angeles 2028, which has in mind a stadium venture not unlike that at U.S. Trials this week and one that may well set a big modern standard but won’t top 1908.

The record before London 1908 was held by Athens 1896, though there was no pool: crowds of “more than 20,000” lines the banks of the Bay of Zea near Pireaus to watch the swimming events unfold in April, when the water temperatures were yet to warm up: 13C. That’s too cold for the rule book these days but back then, while rowing and yachting were cancelled because of weather, the swimmers braved a choppy seas.

There’s none of that in Indianapolis, a city that has hosted swimming in a stadium before and boasted of a capacity that exceeds that most swim venues. In 2004, Conseco Fieldhouse hosted the 2004 FINA Short-Course World Swimming Championships in October 2004. A 25m, 300,000-gallon competition pool and 174,000-gallon warm-up pool were installed for the duration of the event and a total of 71,659 tickets sold over the four days of racing.

The biggest single crowd at that event was 11,488, which set a record for the short-corse showcase and was the biggest crowd for any swim meet in the U.S. outside the Olympic Games, which were hosted in Los Angeles in 1932 and 1984, the city scheduled to host for a third time in 1928 as the second to do so this century and last, after Paris.

Paris 2024

The Olympics in Paris this July and August will mark the first time the Paris La Défense Arena will host aquatic sports. Two 50-metre pools, the competition tank to hold 660,000-gallons of water, have been installed in the arena and are currently being secured, honed, dressed and got ready for Olympic waters to flow and action in what will be a 17,000-seater venue in Games mode.

The venue marks a departure from previous Games venues in its layout. Only about half of the massive venue will be used for the swimming at the Games but the pool is not placed long-ways with seating either side. Instead, it sits perpendicular to the arena floor, the seating formed around it shell- or fan-like. A giant movable grandstand in the centre of the arena floor (though the pool will appear to be central) will border one side of the pool. Screening will separate pools and parts of the venue that will not form part of the ‘show-ground’.

Paris La Défense Arena Gone Green

At midnight on May 5 this year, just minutes after the last show on the first leg of Taylor Swift’s European Eras tour, Paris La Défense Arena in Nanterre went into deconstruction mode in preparation for rebirth as the swimming venue for the Olympic Games in the French capital this summer.

A month after Swift flew from her tour, Myrtha Pools has provided a glimpse of progress in the construction of the 50-metres, long-course, competition pool at the heart of an extraordinary multi-purpose venue, in terms of capacity, scale and technology: 13km of stands, a 5,500-tonne framework, and 28,632 square metres of courts and pitches.

The facility, designed by architect Christian de Portzamparc, opened in 2017. Since then, it has welcomed more than two million spectators to events, including concerts, conventions, seminars and other spectaculars, including rugby matches and other sports events. It will make its Olympic swimming debut in July.

Two Olympic swimming pools are being built: the racing venue and, behind a temporary curtain dividing the inside arena in half, the warm-up/warm-down tank. They’re 2.3m deep, are fitted with underwater cameras and each pool will take three days to fill. After the Games are done, the water will be channelled into La Défense district’s heating network and the pools reconstructed as 25-metre, short-course, tanks for local community centres in France.

The five rings have already been mounted in place at a venue with plans to become ever more sustainable. While Paris La Défense Arena’s roof is decked with 34 solar panels dedicated to powering an adjoining brewery, the management aims to reduce energy consumption at the venue by 40 per cent and achieve an 80 per cent recycling rate by 2025.

High-tech thermal and acoustic insulation already helps limit the facility’s energy needs by keeping the place at consistent temperatures of 16 to 25C. Instead of conventional air conditioning, it relies on a cold water system that releases chilled water vapour to keep audiences cool.

The building also collects rainwater, EuroNews Green reports. The downpour is funnelled into an 800-metre cubed storage tank under the car park and then used to water the synthetic lawn (the moisture helps reduce burns and injuries among rugby players).

Meanwhile, a footnote on the marathon in 1908: The finish line was drawn at precisely the point where Queen Alexandra was to be seated in the stands.

That Royal prerogative and privilege is why the official Olympic marathon stands at “about” 25 miles or 40km. The 1908 organisers decided on a course of 26 miles from the start at Windsor Castle to the royal entrance to the White City Stadium, followed by one lap (586 yards 2 feet; 536 m) of the track, the runners to finish in front of the Royal Box.

The same course was later altered to use a different entrance to the stadium, followed by a partial lap of 385 yards to the same finish.

The modern 42.195 km (26.219 miles) standard distance for the marathon was set by the International Amateur Athletic Federation (IAAF) in May 1921 as a direct result of the length of the course settled on for the 1908 Games at White City in London, with its 100m pool and crowd attendances never since repeated for a swim meet.