What We Will Miss: Planet Phelps & The Pantheon Built By Bob & The GOAT 2000-2016

For the first time since 1996, the Olympic Games will not feature a boy and then man called Michael Phelps. The American GOAT will be entertaining home audiences as a guest commentator for a few sessions of the swimming, while his mentor Bob Bowman is in Tokyo as a team coach and guide to some of his personal charges at the Sun Devils, Arizona State University.

Life goes on but as we await the start of racing in evening heats this Saturday in Tokyo on day 1 of 9, we recall some notes from my archive, penned as Phelps bowed out after another stunning Olympic campaign at Rio 2016, sixteen years after he finished fifth in the 200m butterfly final at Sydney 2000, aged 15.

Ahead of out Tokyo previews tomorrow, a Quick recap:

When Phelps broke his first World record, over 200m butterfly, a year after making his Olympic debut with a fifth place in that event at the age of 15, Australian head coach Don Talbot was asked whether he might challenge Ian Thorpe for the crown as ‘best swimmer in the world’. Talbot said: “Well, he hasn’t achieved anything yet. Longevity is the key to greatness.”

The American slapped a poster of Thorpe on his wall and, for a while, stared it down until the job was done. By the time he retired after the Rio 2016 Olympic Games, Phelps had built a pantheon of Olympic pantheons, with a record 23 golds atop 28 medals, a record 39 World records in the mix, including freestyle, butterfly and medley. Nothing in history comes close.

But at London 2012, he lost his signature event by a whisker, South African teenager Chad le Clos the first to fell Phelps in Olympic waters since he claimed seven golds at Athens 2004 and a record eight golds at Beijing 2008. Phelps retired but could not move on in life until he had the 200m butterfly back in his vault.

At Rio 2016, he did just that with a performance that had it all: toil, determination, revenge, salvation, perseverance and intense, competitive bloody mindedness. He merged from victory to say:

“Just to be able to see the No 1 next to my name again in the 200 ‘fly, one more time: couldn’t have been scripted any better. I told Bob [Bowman, his coach] when I came back how bad I wanted that 200 ‘fly. I came in on a mission and that mission was accomplished.”

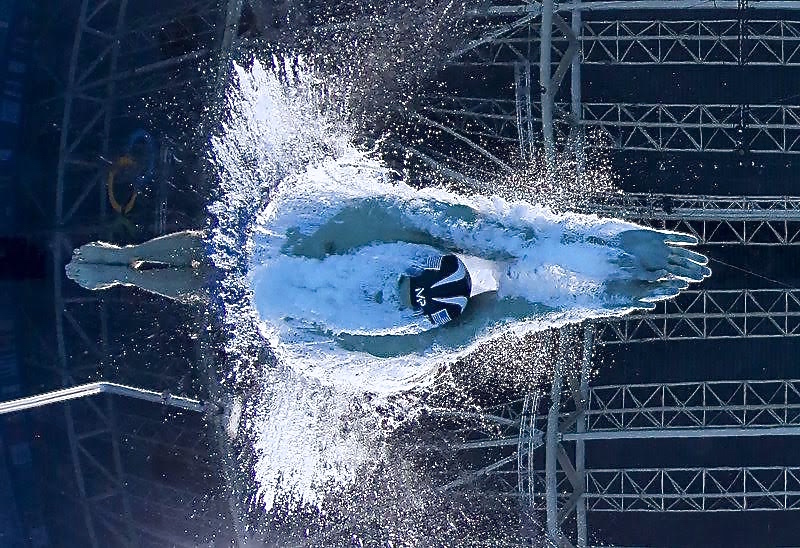

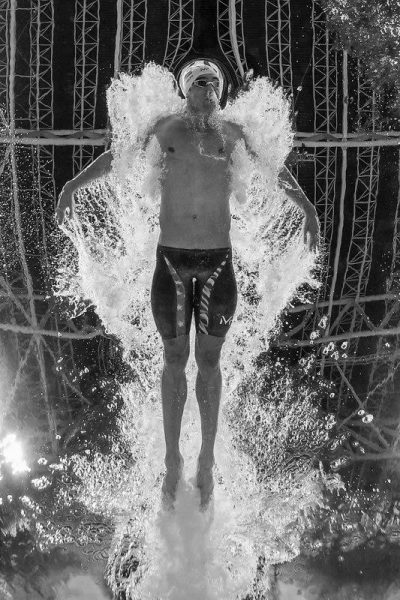

Michael Phelps – image by Patrick B. Kraemer

As amazing as Le Clos’ win had been in 2012, there was a sense in 2016 of a lost jewel in a crown finding its way home.

2016 Archive:

Planet Phelps & The Swim Symphony Composed By Bowman

The maestro behind the greatest medals movement in Olympic history is Machiavelli with a stopwatch.

Michael Phelps, 31 and 20 years into his partnership with Bob Bowman, was not far wide of the mark when he described as “insane” his 23 golds atop 28 medals in all at four Olympics 2004-2016 after it all began with a fifth place in the 200m butterfly final for a 15-year-old at Sydney 2000.

Planet Phelps ranks 5th among nations on the all-time swimming medals table at the Olympics since it all began in 1896. Stretch it to all sports and he makes the top 40 nations.

The grin of a mad scientist breaks out Bowman’s face as he revealed the terrible truth the day after Phelps had past Spitzean heights with an eighth gold medal at Beijing 2008: “At the Melbourne World Cup in 2003 I stepped on his goggles – deliberately. He said ‘hey, someone stepped on my goggles’. I said ‘Oh … well, you’re just gonna have to go without them’.”

In Phelps, Bowman found the raw materials that he had been looking for at the North Baltimore Swim Club. “At 11, he was so fast, he had to swim with older swimmers … but by the end of the practice, and at the most difficult part of the session, I saw a little cap moving up forward to the front of the line with each repeat swim. It was so remarkable, I’d never seen anything like it and when I went home that night I couldn’t sleep I was so excited, but of course I didn’t tell him that.”

Instead, Bowman piled on the metres and challenges. After one particularly bruising practice, Phelps leapt out of the water and started splashing water at some of the girls watching nearby. “I said ‘you should be very tired, that’s the hardest practice you’ve ever done’,” Bowman recalled.

“I’ll never forget, he looked me straight in the eye and said ‘I don’t get tired’, so I made that my life goal to see if I could accomplish that.”

Bowman set about teaching the Baltimore Bullet how to keep loading his gun even as enemy fire keeps raining in, as it does in the Olympic cauldron.

When a scrawny, gangly 12-year-old raced at his first national junior meet in the United States, Bowman noticed he had left his goggles behind just before he walked out to the blocks. “I saw them sitting in our team area, I could have taken the goggles to him but I decided to keep them and see what he could do,” Bowman said.

“So he swam and won the race without the goggles just like he would do in Beijing in the 200 butterfly when his goggles filled with water. He was ready years before.”

Bowman built barriers for the young Phelps to find his way over. “I’ve always tried to find ways to give him adversity in either meets or practice and have him overcome it,” said the coach. When Phelps was 14, Bowman sought out a competition where racing was held late evening. As Phelps raced, Bowman had a word in the driver’s ear: “Make sure we get to the hotel 10 minutes late.”

“Well, guess what,” says Bowman with a chuckle. “That way there was no dinner – he had to deal with it. He’s used to handling pressure situations in training, where that pressure comes from me.

“We have often put him in a situation where practice is not over until he achieves a certain time. Things have to be done absolutely correctly or we do them over.”

Bowman learned some of his tricks and tactics from former Britain performance director Bill Sweetenham. “I was at the AIS [Australian Institute of Sport] when Bill was there training a squad of juniors. After one session, they all complained that the water in the water fountain was too hot. So the next day, there was no water fountain.” Sweetenham has had a builder remove it overnight. “I wouldn’t want you drinking water that’s a little bit too warm,” he told the swimmers. From then, they had to bring their own bottles “and be responsible for that”.

Bowman took Phelps to junior meets where “he would race three times in the morning, three in the afternoon and then I’d say to him, ‘that’s not quite right, you could go again’. Every time he got out and said ‘I’m tired’, I said ‘no, no, look, let’s just try that again, go on now’, and every time he’d get back in and go again.”

In Rio at the last press conference of his career as a racer, Phelps was asked to explain his success. He said:

“My success is nothing out of the ordinary: goal-setting, believing in myself and not giving up until I get there. Sure, I went through ups and downs, in and out of the pool, but not giving up was instilled in me at a very young age. I was in pretty good physical shape for these Games but I had to get my mind right. I said to Bob, I will never let myself get to 230 pounds (104kg) again. I will stay in some kind of shape. The last two Olympics it hasn’t worked, hopefully this time it’s a triumph.”

He takes with him “so many incredible memories” that selecting his favourite things is like trying to digest a meal before eating it.

The menu includes 23 golds. Which one to pick as the standout?

“This Games hands down it was the 200 ‘fly. That might be one of the greatest races of my life. How deep I had to dig, and how bad I wanted it back after 2012. I’ve been on the good side of some of those close ones. As a whole, I don’t know, every Olympics has been so different.”

It was: five golds, one silver behind Joe Schooling, the pupil who became the master and one of waves of younger swimmers revealing all week long the photos (Ryan Murphy from 2004), the posters on the bedroom wall (Olivia Smoliga, you’re not alone), the inspiration that fuelled and drove (Katie Ledecky, Adam Peaty and James Guywatching telly in between reading Harry Potter and project week at primary school). Phelps has been the golden snitch of swimming, the hare and draw in inspiration.

“I saw a picture with me and Ryan when I was on a ‘Swim with the Stars’ tour in Atlanta in 2004,” says Phelps.

“All these photos are showing up, that when I was 19 or 20, and they were eight, nine, 10, so being able to share those memories and being on my last team with them – it’s exciting to see what the future will bring. We have a lot of talent. It’s not one or two or three countries, it’s everybody. I am very proud to see it that way, and hopefully it continues to grow.”

Michael Phelps – Images: Joe Schooling, who played Jack To The Giants whose gold he ‘stole’ at Rio 2016 – images by Patrick B. Kraemer [inset, when Phelps met Schooling the schoolboy – courtesy of Joe Schooling social media)

Timely Instinct

The boy Phelps had a built-in clock. Bowman asked him to write down the times he wanted to achieve in three favourite races. “He was just 11 but six months later he swam those exact times, to the one-hundredth of a second,” Bowman recalled. “He always had a very good sense of finding where he wants to go and how to get there.”

Goal-setting became a daily habit. Bowman explains: “On a daily basis I remind Michael of what his long and short-term goals are and how he stands today in relation to that. That’s where that whole thing comes in where many say ‘I’ll deal with it tomorrow’. I’m there to say no, let’s deal with it today. That’s my job. When we’ve had tempers flare, that’s where the issue is.

“He may not be ready to face that at that time and I make him do it or get him to a situation where it happens. There’s a lot of work that goes into it. There are a lot of ups and downs. He has bad days just like everybody else.”

Canadian medley ace Marianne Limpert trained in Baltimore for a stretch and told Bowman: “I’m so glad I’m training here…I just though Michael was like a little swimming robot but now I see he’s a real person, he has his good moods and bad moods. Even when he’s in a bad mood he channels it into effort.”

“One of his best attributes”, says Bowman, whose role has been pivotal, critical even: up to Beijing there had been 12 years of emotional, mental and physical preparation of a kind that few could have withstood. London 2012 was not what he wanted it to be; it proved too much for him to get back up after the soaring of 2008 and the gladiatorial battles of 2009. But the button marked “driven – do not touch” is as much a part of the Phelps build as a stripe is to a tiger.

Bowman called Phelps “The Motivation Machine”, with “good mood, bad mood, happy or angry, channelled into effort to take him to new places. That’s one of his best attributes.”

Asked what he had wanted out of Rio 2016 and a fifth Games beyond the medals, Phelps said: “I wanted people to see the real me. I can’t wrap my head around it. I’ve lived so many incredible things. I’m at a loss of words.” What he wanted was “to make swimming the big sport it deserves to be. I want to change swimming”.

He will be an assistant coach to Bowman at Arizona State University, while his eponymous swim school and foundation. You might also expect to see Phelps lead swimmers into a more professional era worldwide in the coming years.

The Nuance of Numbers

At 23, the gold count matched the most iconic shirt number of them all in American sport. Phelps beamed broadly and said: “I guess everything happens for a reason. Obviously, you guys know, Michael Jordan has been an inspiration for me throughout my career. Watching what he did in the sport of basketball is something I’ve dreamed about doing in the sport of swimming. We’ve done a lot, but there is a lot more work to be done. I was thinking about that today, after the relay. Number 23 will always be a special number. It always has been, and now it will be even more special.”

Phelps’ is moving on; no coming back this time: “I’m in the best place possible, this (Rio 2016) is the cherry I wanted to put on the cake. When I came back (out of retirement in 2013) I wanted to see how much more I could do. I don’t have anything else left.

“I have a new future – the list is endless of things I want to do. This is it. This is the last time you’ll ever see me racing in the water again. That’s why the emotions took over me last night, trying to wrap my head around 28 Olympic medals. I woke Boomer (3 months) up (when I got back to the Olympic Village), which Nicole [Johnson, the partner he married in secret before the Games] wasn’t happy about, but I wanted to hug my son.”

Michael Phelps – photo by Patrick B. Kraemer

Where did fatherhood fit? “It’s the most important thing in the world. Being apart from him for these past four weeks, from when I saw him last, he’s changed so much. I changed a diaper last night. It was so nice to see him smiling back at me. I want to be there every step of the way, I don’t want to miss a thing.”

He no longer feels he will miss swimming, at least not the racing. He’s done with that and coach Bowman knew it, too. Raise family – and that is what Bob Bowman is to Phelps – on the approach of this full moon, and we find the GOAT at his most vulnerable and tenacious.

“Bob – he knew it was over when I walked over to him in the last warm-up,” said Phelps. Passion runs deep, his eyes well, he has to hold himself in check, pauses, swallows hard and sighs.

In his mind’s eye he sees all the warm-ups in one, a planet of workouts and challenges, goals set, goals achieved. He cannot “wrap my head around it”, the medal tally alone “insane”. He stares down at wringing hands that have pulled more fast water than it takes to swim round the globe.

“Without Bob, I would not be in this ball park. He’s been with me through good and bad and mostly it was really good. He helped get me to this point … he’s been a father figure to me and helped me through the work. He’s been there every step of the way.”

Their deeper understanding no longer requires words of reassurance. If in London 2012 they talked much about this being “the moment to go, the last time, the last session”, then “last night we really didn’t talk much … we didn;’t have to”.

Bowman “was probably more emotional than I was, said Phelps. “He was walking up and down every 50 [lap] I did. I’d look to the right then to the left and he’d be right there. A couple of times I smiled. I was just enjoying the process and the last race.”

Phelps repeated a line he used back in London, when he told Bowman that he had goggles so no one could see his tears but the coach had glasses and everyone could see just how much it all meant to both men.

Asked what the future held, Phelps said: “I want swimming to be a lifesaver. Too many people have lost their lives to drowning incidents and that’s a big passion of mine. I want more kids to be water safe, to do whatever I can to stop that from happening. If I can teach more kids to swim, then I’ve been successful.”

All In The Mind

Not quite but so much at the very pointy end of business comes down to that among those who are supremely fit, mostly very ready to be the very best they can be and yet, come the hour, knocked by stage fright and diminished by the moment, sometime painfully so, as the past week showed all too brutally.

Asked about the USA Vs Australia rivalry and what might have been as the USA romped home to superpower status once more, Phelps said: “Australia have always had fast swimmers. I guess I expected them to swim well. I have no idea what happened, but the talent’s there. I don’t know if I could give any advice. Maybe it was a mental thing.” He had a tip to give:

“I read a book this year – I read another book this year (he laughs and says ‘I don’t read many books, as some of you know’) – The Power Of Your Subconscious Mind (by Joseph Murphy) – just to see what it was about. Always staying positive and believing in yourself goes a long way. Your mind is a very powerful thing and a lot of people don’t realise how truly powerful it is.”

It will take that and more if anyone is ever going to get to those 28 medals and 23 golds. Not in our lifetime, many believe. But did the man himself believe it would happen in his time?

“I don’t know. I think the craziest thing is the longevity of my career. That’s why I’m here. I’d love to see somebody challenge it, we love to see records broken. How many years did people go thinking nobody could ever beat (Mark) Spitz [7 golds, Munich 1972; 8 golds, Phelps, 2008].”

Who recalls a dream that turned to goal and then to achievement and the reward and happiness that goes with it, be that a relationship, a piece of work, a garden built, a journey travelled? Says Phelps:

“I’ve lived a dream come true. Being able to cap it all off with these Games, it’s just a perfect way to finish.”

Bowman, a grandad figure to Boomer Bob Phelps, 3 months, was asked if he could find another Phelps out there. He guffawed and said: “Absolutely not. I’m not even looking.

“It’s not even in a generation, it’s once in every 10 generations that someone like Michael comes along. He just had so many things going for him – he had the physical skills, the mental outlook, the family that supported swimming, he was in a great swimming club. He had the emotional ability to get up for big races, and be able to perform better under pressure. I don’t think you’ll be seeing another Michael. There is only one Michael.”

The Eighth Symphony

And for your next trick? That was the question for the aquatic maestro and magician back on August 22, 2008. In the wake of conducting his 8th Swimming Symphony with Phelpsian Beijing, a corner of Bob Bowman’s mind was already at work. It might be February 1, 2009 before the swimmer got back in the water, said the coach, Phelps having been promised a long break if all went well. All had gone exceedingly well. Better, indeed, than any other Olympic campaign in history.

He needed rest. Even with a February 2009 return on the cards, Bowman believed that Phelps would be back in time for Rome 2009 world titles. “He can’t sit still for long,” Bowman told me in his last interview before he boarded a plane for home. “It’ll be like his welcome back meet, a little like Montreal (2005),” he added, dreaming of sunny days in the Eternal City.

We’d seen the sun the day before inside the Water Cube. And the moon and the stars and all the planets on a tour of the aquatic orbit of a truly unique human being, a man whose achievements come straight from the book of comic-strip super-heroes. Spirits soared at the sight of it all.

Michael Phelps referred to being “almost half way through my races” after taking the 200m freestyle crown in a world record of 1:42.96, the pace of a panel or two of polyurethane on the way to a full shiny crisis.

It was after the 200m free that the 8th Symphony was starting to find its way into the soul. With each passing race, a few more notes were heard. Beethoven‘s Ninth, Mozart‘s Clarinet Concerto In A, K 622 – 2, Adagio, Rodrigo‘s haunting Concierto de Aranjuez. “How did you get that? Bowman asked me after I noted the Spanish composer’s haunting work in my report of the 200m freestyle final.

It was there for all with an ear for the water to hear, for all with an understanding of swimming and its element to feel, to see: the balance, the rhythm, the beat, the drop, the harmony in between. The sparkle of symbiosis between water and the swimmers whose bodies are 60% made of the same fluid. How could they not get on?

The uplifting beauty of it all; movements, orchestral and aquatic. In all the years I had (and have) watched swimming, I could not recall witnessing something quite so complete, quite so certain even when the call was closer than the eye can count and the clock is judge.

Time up, tolled the bell for Nurmi, Latynina, Spitz and Lewis half-way through the Symphony at the count of nine all-time career Olympic golds. The ensemble was just getting into its swing as nests came from the office of a newspaper I work for that an editor had said he’d got “bored” with the “inevitability of it all”, a few nods of agreement among responses. Like jokes, great events sometimes require you to have been there. After the 200m free, my colleague Nicole Jeffery, of The Australia, noted that even for a man who performs five miracles before lunchtime, Phelps had excelled himself.

Bowman had told him that he should and could get his feet on the wall at 50sec half-way. Yes, sir – will do. We’d seen it before, at Melbourne 2007 worlds in particular, but the sight of Phelps on a roll was something to behold.

When he rolled and streamlined and drove and dug, Phelps moved like a killer whale settled on sealing the fate of a seal marked supper. Latent power and controlled aggression combined with an accuracy of thought and calculation, timing and tenacity steely and cutting in nature. Watch the cupping of Phelps’s hand, the roll of the whole arm and shoulder over an invisible barrel as he harnesses his element, an invisible yoke to transport him through translucence. Warp-speed, second star on the right, straight on ’til morning kind of stuff.

Phelps emerged from the 200m gold in Beijing to note that loss in the same event in that “race of the century” with Ian Thorpe and Pieter Van Den Hoogenband at the 2004 Games in Athens had put the fire in his belly for what unfolded this morning.

“I hate to lose,” said Phelps. “And getting third in the 200 free four years ago…You know, when I do lose in a race like that and in circumstances like that, it motivates me even more to try and swim faster.”

On drawing level at nine career golds with the all-time record holders, Americans Mark Spitz, Carl Lewis, Finland’s Paavo Nurmi and Soviet gymnast Larysa Latynina, Superfish said: “To be tied for the most Olympic golds of all time, with those names in Olympic history and the Olympics have been around for so many years, is a pretty amazing accomplishment. It’s pretty cool. It’s definitely an honour. I’ve been able to spend some time with Carl Lewis and exchange a few words with Spitz here and there, so it’s pretty amazing.”

Ahead of him at that stage: the 200 ‘fly final, the 4x200m free relay, the 200IM, the 100 ‘fly against Ian Crocker and the 4x100m medley that would draw him level with Spitz – or not – and keep the possibility of eight alive – or not. Turned out that not was not part of his vocabulary.

The coach needed to say very little come the big moment, the work having been done long before leaving home. Even so, there were moments when Bowman needed to be hands on in the full glare of the lights. In Beijing, that moment came on the day of the 200m medley – job done – and the 100m butterfly semi soon after. After the 200m medley, Phelps returned to his coach “totally drained”. Said Bowman: “I had to talk him through that. He was really tired at that point. I wasn’t sure how it was going to go.”

Phelps got through it and the next day took the 100m butterfly gold 0.01sec ahead of Milorad Cavic, of Serbia. Ill-feeling followed when Serbian team officials challenged the result, suggesting that Cavid had touched first but that his pad had not registered. Conspiracy theories suggested that Omega had stopped the clock themselves in favour of its poster boy. The truth was to be found elsewhere, while the controversy required Phelps to stay focussed, his job not yet one.

Bowman later noted that Phelps “can focus like no other athlete”. “Phelps stares down Cavic” said one headline and accompanying photo-caption. Not so, said Bowman: “If you were watching the 100m butterfly final, the Serbian swimmer and Michael were facing each other standing behind the blocks and it looked like they were trying to stare each other down. After the race I asked Michael if that was what he was doing, and he said ‘I didn’t even know he was there’. That’s how focused Michael is on what he wants to do.”

The 100m butterfly result flicked a switch for the coach. Said Bowman: “The biggest moment of relief for me was after the 100m butterfly [final]. I’d convinced myself that seven was the number. It wasn’t until the last 15m [butterfly] that I thought maybe it [eight] would happen. One thing Michael does better than anyone else is to use the right amount of emotional energy for every race he stands up for.”

And stand up he did, teammates with him to deliver the eight. The water whipped, the gold count towering, the symphony complete, Bowman said that Phelps would branch out into more sprints, more backstroke, some more breaststroke at national events, no 400Im, as agreed with Phelps, and while the 400m free and a shot at Thorpey’s standard was not on the cards, the signature 200 ‘fly would remain all the way back to the blocks at London 2012.

In Beijing, Bowman had witnessed the very thing he did not expect to see but had, nonetheless, prepared his pupil for many moons before risk turned to robotic response just when it was hosted needed on the biggest of occasions: Phelps’ goggles had filled with water at the start – and he had struggled to find best form. The result was still a world record of 1:52.03, the suit, perhaps, having made up for the loss of vision. Bowman had thought a time “in the 1:50s” had been possible that day.

The impact of suits had not yet become clear and Bowman was talking of a sub-50 100 ‘fly as being in the realms of possibilities for Phelps. It would happen, in a LZR Racer, too, in a Rome Circus that would sink the shiny suits for good, a January 1, 2010 deadline for death to buoyancy set after Bowman said his boy would not be coming to the FINA party unless the hosts got back to swimmer and swimming, not industry and impostor.

Even so, Bowman was among those who would later say that much had been learned from the experience of suits and the catch-up with the clock might be swifter because of the knowledge gained even with the artificial aid had been lost. The role of coach and swimmer fits well with the thought of George Bernard Shaw:

“People who say it cannot be done should not interrupt those who are doing it.”

Craig Lord’s Favourite Phelps Olympic Solo Medal Moments

All of Phelps’ wins were tremendous, of course, including the non-Olympic variety, the 2007 World Championships in Melbourne a soaring campaign flush with outstanding swims. Here’s my ranking of favourite Olympic medal moments – and a brief why:

- 200m butterfly, Rio 2016 – Gold. As Phelps poked his head through a curtain stage left and folk started to wonder whether he might be a boy fit to grab Ian Thorpe‘s headline-grabbing power away, Don Talbot said: “Well, he hasn’t achieved anything yet. Longevity is the key to greatness.” Phelps slapped a poster of Thorpe on his wall and stared it down every day until the job was done. In Rio after reclaiming the crown – the very spike of his return – he said: “Just to be able to see the No 1 next to my name again in the 200 ‘fly, one more time: couldn’t have been scripted any better. I told Bob when I came back how bad I wanted that 200 ‘fly. I came in on a mission and that mission was accomplished.” No disrespect at all to Chad Le Clos but there was a sense of a lost jewel in a crown finding its way home last week in the 200m butterfly.

- 400m medley, Athens 2004 – Gold. First gold; first WR at the Olympics – at 19. It was thrilling, a herald for the greatest haul – and how – in Olympic history. The biggest winning margin in history. Here was the evidence that we were looking at the versatile swimmer to end them all.

- 200m freestyle, Beijing 2008 – Gold: we all know that the suits made a difference, to Phelps, too; and most of you know how I felt about those suits. And then there was a 1:43.86 on the clock – and then there was a 1:42.96 on the clock. It was a part of those pieces of eight. We will never know where the clock might have been. We do know he would have won. We do know that he would have done so convincingly. And we do know that he swam that race as masterly as they come four years after enduring so that progress could be made.

- 200m freestyle Athens 2004 – Bronze: the ‘race of the century’. Well, it won’t be by the time the century is up, four years into 100 years not the best of moments to dismiss 96 years of achievement to come. Still, what a race and with Ian Thorpe and Pieter Van Den Hoogenband ahead of him, Phelps had the best gift he could have had in terms of the next four years in pursuit of those pieces of eight.

- 200m butterfly, London 2012 – Silver: same spirit as above. It is because Chad Le Clos got his hand to the wall a touch ahead in London that we were all able to witness the wonder of Rio 2016.

- 100m butterfly, Beijing 2008 – Gold: 0.01. Nailing the finish. Knowing where he must be relative to Milorad Cavic if he was going to keep the dream of eight alive. So memorable that Phelps and Bowman named a thoroughbred racehorse they co-owned ‘By A Hundredth’ (not quite a nag … but then you can’t win ’em all 🙂

- 400m medley, Beijing 2008 – Gold: gain, the bloody suits get in the way. We will never know where he would have been on the clock. Chances are it would have been equally impressive. As things stood, it was 4:03.84. Mind-boggling. The top speed of Janet Evans and Rebecca Adlington when they claimed 400m free Olympic gold, with breaststroke in the mix. Take a timewarp and place Phelps, 2008, at the height of his powers in a lane next to Brad Cooper, Steve Genter, Tom McBreen and Graham Windeatt, 1972 – and he’s right on their tail using all four strokes.

- 200m medley, Beijing 2008 – Gold: the world record may have reflected the suit a touch, such was the season but look at the dominance: 2.29 up on Laszlo Cseh, 2.30 up on Ryan Lochte (who’d just won the 200 back). Phelps led from go to gold. Another masterclass.

- 200m medley, Rio 2016 – Gold: founder member of the Quad Club. History in the making. And again, 2sec ahead. Dominant at 31 – the oldest solo Olympic champion in history (until Anthony Ervin changed the game).

- 200m butterfly, Beijing 2008 – Gold: look not at the clock (though it was a WR that will stand for some while yet), look at the goggles filled with water; see a mind blind but able to see his way to each wall by counting his strokes and nailing his walls and keeping Cseh at bay once more.

- 100m butterfly, Athens 2004 – Gold: 0.04 ahead of Ian Crocker. Stunning for that alone but sensationally so for how it unfolded – and then part of a lore when Phelps said ‘I’d like Ian to go in the medley relay final’. ]

- 100m butterfly, London 2012 – Gold: he hadn’t put the work in/didn’t find the right spike to get what he wanted out of the 200m in London but the 100m he was not prepared to give up, under any circumstances. Knocked down a few times … but not out. Never out.

- 200m medley, London 2012 – Gold: The 400IM – 4th. Shocker. Up from the groud, Phelps rose, shookm off the dust, licked the wound and took stock. Not again. And not again in the face of Ryan Lochte as a medley man on a roll, the first shiny suit standard downed by his gun.

- 200m butterfly, Athens, 2004 – Gold: It was the first of his 200m butterfly wins after he had taken the world record at 16 in 2001 and then the world title in 2003. An Olympic record, the Midas Touch with him.

- 200m medley, Athens, 2004 – Gold: He’d demolished the world record in 1:55.94, so a 1:57.14 win seemed modest. It was anything but, of course. His fourth gold medal of the Games and career was his 1.674sec ahead of Ryan Lochte, a towering duel in its infancy.