WADA Tested On State Of Independence In Go-Free-23 Chinese Doping Positives Inquiry

As the Go-Free 23 Chinese positives saga pours on to the canvas of doping controversies, old patterns have started to emerge, including a closed training camp in May (we assume not closed to anti-doping testers) and connections in the investigation called by World Anti-Doping Agency – WADA – that are too close to comfort if ‘independent’ is to hold hands with trust.

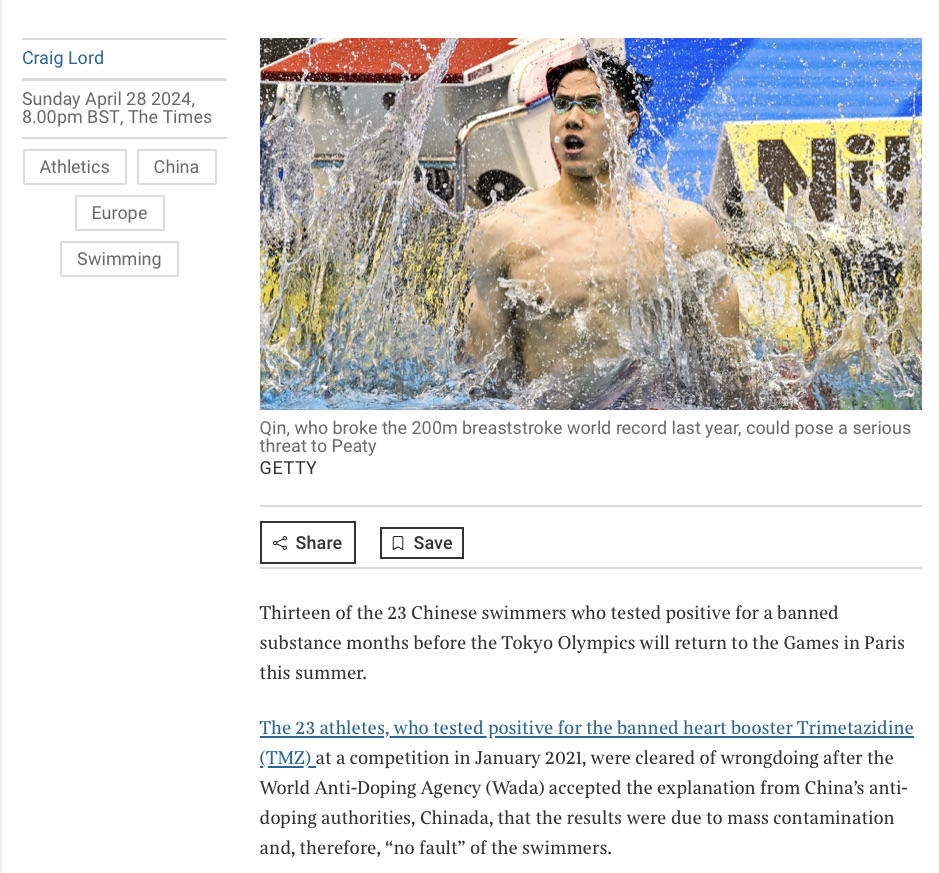

The Chinese team, on its way to Paris with 13 of its swimming squad under a cloud and in the cross hairs of athletes and others around the world after they and 10 others produced 28 positive tests for the banned heart-booster trimetazidine in early January 2021, will be in Shanghai behind locked doors from next week in preparation for Paris.

For most of the 13, they will head to Paris three years after having competed at the Tokyo2020ne Olympic Games that July and August after WADA agreed with Chinada and Chinese state security agents that the 23 positives were a “no fault” case of mass contamination caused by a heart booster that somehow made its way into a spice container at the hotel kitchen during or before the competition from January 1-4.

No-one knows who put the banned substance there, how it might have got there by accident nor even how it was possible for a sealed tablet hard enough to withstand impact from being dropped from a height of seven metres to impact with a stone floor.

Those are just some of the questions being asked by the journalists at the ARD in Germany, New York Times, the two organisations that worked on the investigation that revealed death of disturbing developments, and News Corp, which broke the story early on the morning of April 20. Those questions remain the tip of an iceberg of issues that WADA and its ‘independent investigation’, called last Thursday, must address. More to come on all of that and matters that have not yet been raised.

Meanwhile, my teammate and Chief Sports Reporter at The Times, Matt Lawton, is on the trail of matters that test the term ‘independent’ and shake it to its very core.

This morning, The Times reported that the prosecutor appointed by WADA for its independent investigation worked closely for more than a decade with the auditor who praised the agency’s intelligence and investigations department that year for its “incredibly impressive and strong work”.

Eric Cottier, a retired Swiss prosecutor from the Vaud region that is home to the IOC, World Aquatics and European Aquatics, among many other Olympic sports organisations, came under scrutiny the moment he was named by WADA last week.

Travis Tygart, the chief executive of the United States Anti-Doping Agency (Usada), accused the global clean-sport gatekeeper of recruiting a “cherrypicked attorney from its own back yard”.

Cottier, who spent more than 17 years as the attorney general of Vaud, a regular host and donor to WADA’s annual symposium, has been defended by the agency, which notes that state and judiciary are separate in Switzerland and regional funds donated to a WADA event have nothing to do with the judiciary.

Still, the criticism persists and the loss of trust is to be found far beyond Usada, who’s boss said the global gatekeeper intended “to pull the wool over our eyes” with the appointment of Cottier from a judiciary that has handled a great many sporting disputes in Olympic sport down the decades.

As The Times noted: Wada has fiercely rejected any suggestion that Cottier lacks independence. “This plainly does not cast any doubt on Mr Cottier’s independence and impartiality in this matter,” a Wada spokesman said.

On The Trail Of Close Connections To WADA

However, The Thunderer points out today that Jacques Antenen, who has revised WADA performance as an “independent supervisor”, carried out the audit of the WADA investigations department that reviewed the findings of Chinada in the case of the go-free 23.

Lawton reports: “Until June 2022, Antenen was the commander of the Vaud cantonal police, a former investigating judge of the canton of Vaud and a special federal prosecutor of the Swiss Confederation. He was head of the Vaud police department for 13 years, and during that time worked closely with Cottier in his role as attorney general.

“When a function was organised to mark Antenen’s retirement as police commander two years ago, one Swiss newspaper said that there were 200 guests. Among them were Cottier and Christophe De Kepper, the director general of the International Olympic Committee, which is Wada’s principal funder and has five seats on Wada’s executive committee.”

“Seven months before, in December 2021, Wada published Antenen’s conclusions from that year’s audit of the investigations department.”

The department director, Gunter Younger, thanked Antenen and said: “This is the fourth year in a row that he has been satisfied with the quality of our work and this report is another boost for us as we strive to protect athletes and clean sport around the world.”

Yet again, WADA rejected any concerns over relationships and independence.

Read The Times article in full, including the WADA response and the views of a leading anti-doping lawyer who has reviewed the WADA conflict of interest policy and also raises concern about Cottier’s appointment. WADA Policy:

“… an appearance of a conflict of interest exists when it is reasonably likely that an informed observer may perceive a conflict of interest”.

“The really important thing about conflict policies is that they maintain trust and confidence in decisions,” said the lawyer, who at this stage would prefer to be anonymous. “But how things look is as important as how things are, which again is why the perception of conflict is so important.”

As the gap between what constitutes a risk of conflict of interest and lack of independence in sports governance and the wider world at large appears to widen on Monday, the Team USA Athletes’ Commission wrote to Rahul Gupta, the director of the US Office of National Drug Control Policy and an executive committee member of WADA, to note that a “lack of transparency” had “undermined” their “confidence” in the global gatekeeper.

The Cottier investigation was a “check the box exercise”, they added, while calling for a “truly independent investigation” and an “independent review that results in greater independence and oversight of Wada”.

The World Players Association (WPA) weighed in today, interim executive director, Matthew Graham, saying: “Longstanding systemic issues have plagued the anti-doping movement. Athletes have faced unjust processes and sanctions, while officials have not been held to account. The response to this scandal must address fundamental root causes, not just symptoms, if Wada is to assert any legitimacy as a steadfast regulator of global anti-doping policy.”

While the row rumbles on, the Chinese swimming team, including 13 of the go-free 23, are on the way to a well-rehearsed approach to the Olympics,, one that was sharpened during the Covid pandemic and a 2020-2021 delayed and distorted Games period in which Chinese swimmers attended at least four staging camps, one of them, between April and June 2020, lasting three months, as China imposed one of the most stringent coronavirus lockdowns in the world.

Another camp preceded the fateful January competition, according to Xinhua reports at the time. That is among questions that WADA appears not to have conducted any of its own inquiries on even though the point may be crucial to understanding when and in what circumstances a banned substance ended up in the bodies of 23 of China’s fastest fish.