The Three-Year Swim Club: From Sakamoto’s Sugar-Cane Ditch To Olympic Waters

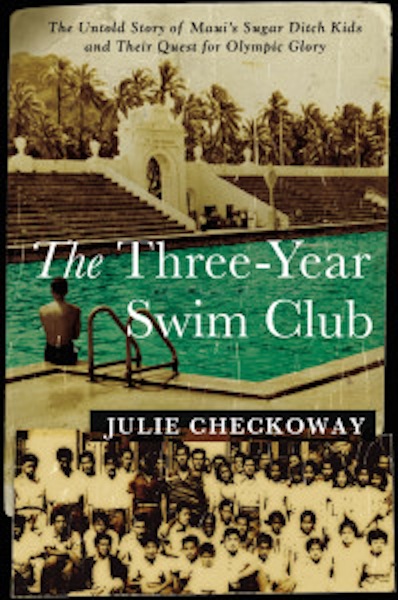

Book Review – The Three Year Swim Club: The Untold Story of Maui’s Sugar Ditch Kids and Their Quest for Olympic Glory. By Julie Checkoway

Julie Checkoway’s book tells the story of a group of pupils whose teacher challenged them to become Olympians. It is called “The Three-Year Swim Club”, it was 1937 and the coach in question was Soichi Sakamoto.

At 30 years of age, the Japanese-American schoolteacher challenged a group of children he had taught to swim on the island of Maui in Hawaii: work hard and in 1940 you will race at the Olympic Games.

The two nations from which he hailed would soon be at war with each other and the 1940 Games would never happen, the racism, bigotry, hatred and brutality of the Nazis sinking the world into war.

The goal, the hopes, the dreams were all very much alive in Sakamoto’s charges, however. Three years to make the USA Olympic swim team. A tall order in any just about any era.

All the more so when you’re the children of workers on a sugar cane plantation and life is far removed from the stuff of plenty, in terms of time and resources financial and other. Against the odds, some of them made it: national champions in 1940 with no Games to go to.

Some even swam on and made it to the 1948 Games in London. Sakamoto trained them in the irrigation ditches of the plantations. He noted that swimming in the ditch gave his kids a couple of advantages: the narrowness of experience reduced room for energy wasting movement and swimming against a current in the ditch made the swimmers stronger.

The tale is outlined in “Aquatics“, the 100-year anniversary book of FINA, the international federation, penned for the 2008 centenary by the author of this article.

The rules of Sakamoto’s club: no smoking; no drinking; no gambling; no swearing; strict daily training; loyalty to the club; and a three-year commitment, no opt-outs.

Bill Smith was one of his charges: he claimed gold over 400m freestyle for the USA at the 1948 Olympics in London. By 1952, Sakamoto had two others on the list of Olympic achievers: Bill Woolsey and Evelyn Kawamoto both won Olympic medals that year.

In 1932, a reporter for the Chicago Tribune named Philip Kinsley visited Maui, and on approach by inter-island aeroplane, he looked down, took in and then later wrote of what he saw:

A place “sculptured green cup . . . rimmed by white Pacific surf lines”. And volcanoes at either side.

In March of 2012, some eighty years after Kinsley traveled to Maui, the author of “Three-Year Club” also saw the island’s lush peaks, but “my destination was the very bottom of Kinsley’s cup, the arid, golden lowland that gave Maui the nickname by which it’s still known today: ‘the Valley Isle’.”

Julie Checkoway writes: “When I first heard of the Three-Year Swim Club, most of it, its stories and its people, had disappeared, and what little of it was left consisted of half-excavated bones that long ago had calcified into myth. There were a few original swimmers left; most were in their nineties and crisp of mind, but after years of “talking story” with each other – sitting together and emphasizing this moment or forgetting that one -the tale they told was a legend that went like this: in 1937, a schoolteacher in Pu‘unene taught impoverished Japanese-American camp kids how to swim in the plantation’s filthy irrigation ditches, and he challenged them to transform themselves into Olympians. That much was true, but was there was more that needed telling, and it was that more for which I’d come nearly three thousand miles to Pu‘unene.

“The school at which the teacher worked now houses county offices— and though just beyond its smudged windows and across the dusty road is the very ditch in which the Three-Year Swim Club had its start, if you stop and ask anyone nearby, no one will be able to tell you about the teacher or the children or the team.

Farther down that road, just past the abandoned Roman Catholic graveyard with its dark toothlike headstones, is the pool; it’s on plantation land, but the sugar company hasn’t kept it up. It’s had no need to: no one really lives in Pu‘unene anymore; after World War II, when the mill mechanized and laborers unionized, the camps emptied of workers who fled the island or moved on to real houses in a nearby subdivision known as “Dream City”.”